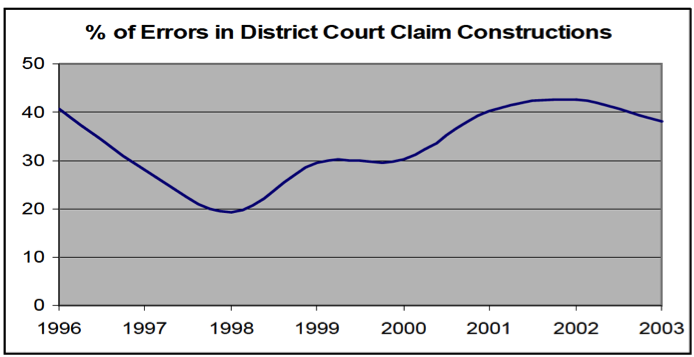

So when the Supreme Court granted Teva's petition for certiorari in March 2014—and thus agreed to decide whether a district court's factual findings underlying its claim construction decisions should be reviewed for "clear error" under Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)—the patent community took notice. To commentators, the Court appeared poised to weigh in on an issue that has long frustrated many: the Federal Circuit's high rates of reversal, vacatur, and remand based on its findings of erroneous claim constructions.[3] The uncertainty caused by those high reversal rates has created widespread dissatisfaction among district court judges, patent holders, technology companies, and some Federal Circuit judges.[4]

Oral Argument

At oral argument, it appeared that frustration with the Federal Circuit's high reversal rate on claim construction had spread to some members of the Supreme Court itself. In response to Carter Phillips's argument that the Court should not unsettle the Federal Circuit's 20-year practice of de novo review, Justice Breyer retorted that the consequence of that practice has been that the Federal Circuit reverses on claim construction "non-stop," citing a 30-40% reversal rate. Justices Breyer and Scalia used their questions to argue for greater deference. They pointed to the language of Rule 52(a), which makes no exception for patent cases, and observed that district courts are uniquely able to observe live expert testimony regarding disputed claim terms, but have no motivation to do so if, ultimately, their factfindings will receive no deference.

"Wishful thinking to the contrary, Teva is unlikely to have significant legal impact on claim construction reversal rates.

Justice Alito argued against a change to the existing standard. Largely ignoring Rule 52(a), he quipped that "this fascinating legal debate" has no "practical significance" and that the game of sorting out which claim construction findings should receive deference as factual findings and which should be reviewed de novo as questions of law was not "worthwhile as a practical matter."

The Court's Opinion

The Court issued its opinion on January 20, 2015, ruling in Teva's favor. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., et al. v. Sandoz, Inc., et al., No. 13-854. Writing for the Court, Justice Breyer explained that Rule 52(a)'s deferential standard "applies to both subsidiary and ultimate facts." Slip op. at 4. The Court then held that a district court's factual determinations based on extrinsic evidence must be reviewed for clear error. Id. at 6. It pointed to the facts of the case before it as "a perfect example of the factfinding that sometimes underlies claim construction: The parties here presented the District Court with competing fact-related claims by different experts, and the District Court resolved the issues of fact that divided those experts." Id. at 10. As a general example of the type of factfinding requiring clear error review, it pointed to a district court's determinations as to "the background science or the meaning of a term in the relevant art during the relevant time period." Id. at 12.

Yet the Court made clear that extrinsic evidence and expert testimony alone "cannot be used to prove the proper or legal construction" of patent claims. Id. Rather, even where the trial court has made a factual determination as to disputed extrinsic evidence, it must still "conduct a legal analysis" before it can construe the patent term, i.e., it must decide how one of ordinary skill in the art would construe the disputed term "in the context of the specific patent claim under review." Id. (emphasis original). And critically, the Court reiterated that the ultimate conclusion of that legal analysis—the trial court's claim construction—will remain subject to de novo review. The Court summarized its holding thusly:

Accordingly, the question we have answered here concerns review of the district court's resolution of a subsidiary factual dispute that helps that court determine the proper interpretation of the written patent claim. The district judge, after deciding the factual dispute, will then interpret the patent claim in light of the facts as he has found them. This ultimate interpretation is a legal conclusion. The appellate court can still review the district court's ultimate construction of the claim de novo. But, to overturn the judge's resolution of an underlying factual dispute, the Court of Appeals must find that the judge, in respect to those factual findings, has made a clear error. Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 52(a)(6).Id. at 13.

Implications and Impact

Wishful thinking to the contrary, Teva is unlikely to have significant legal impact on claim construction reversal rates, though it will likely increase litigation costs due to increased attempts to inject the record with expert testimony and to frame construction issues as heavily fact dependent.

Teva's ultimate impact is limited to circumstances where the trial court construes a patent term based heavily on extrinsic evidence—such as expert testimony, academic or industry literature, or dictionaries. But the vast majority of claim constructions are based primarily or even entirely on intrinsic evidence—the patent's claims, specification, and prosecution history. As the Federal Circuit has recognized, "[i]n most situations, an analysis of the intrinsic evidence alone will resolve any ambiguity in a disputed claim term." Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996). That generalization has thus far held true. A recent study shows that 92.5% of district court claim constructions rely on one or more sources of intrinsic evidence.[5]

And while there is little doubt after Teva that trial courts will now place greater emphasis on extrinsic evidence and factfinding, the ultimate question is whether that trend will impact claim construction reversal rates on appeal. That is unlikely.

The underlying issue of how much reliance a district court should place on extrinsic evidence in a given instance, if any, is a legal question that the Federal Circuit reviews de novo. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit—not the district courts—ultimately controls the extent of Teva's legal impact. Consistent with its precedent, the court will exercise that control to maintain the paramount importance of intrinsic evidence to claim construction. Indeed, the court has previously identified a number of concerns with elevating the importance of extrinsic evidence:

First, extrinsic evidence by definition is not part of the patent and does not have the specification's virtue of being created at the time of patent prosecution for the purpose of explaining the patent's scope and meaning. Second, while claims are construed as they would be understood by a hypothetical person of skill in the art, extrinsic publications may not be written by or for skilled artisans and therefore may not reflect the understanding of a skilled artisan in the field of the patent. Third, extrinsic evidence consisting of expert reports and testimony is generated at the time of and for the purpose of litigation and thus can suffer from bias that is not present in intrinsic evidence. . . . Fourth, there is a virtually unbounded universe of potential extrinsic evidence of some marginal relevance that could be brought to bear on any claim construction question. . . . Finally, undue reliance on extrinsic evidence poses the risk that it will be used to change the meaning of claims in derogation of the "indisputable public records consisting of the claims, the specification and the prosecution history," thereby undermining the public notice function of patents.

Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1318-19 (Fed. Cir. 2005). And in Vitronics, the court went so far as to preclude any reliance on extrinsic evidence where terms can be construed based on the intrinsic evidence alone,[6] though it later retreated from that position in Phillips. Given its caution toward extrinsic evidence, and its demonstrated desire to control patent litigation outcomes, the Federal Circuit will likely marginalize or ignore district courts' enhanced reliance on factual findings in most instances.

That approach would appear consistent with Teva itself, which expressed no intention of elevating the importance of extrinsic evidence. Slip op. at 10 ("[S]ubsidiary factfinding is unlikely to loom large in the universe of litigated claim construction."). Moreover, In light of the Supreme Court's recent decision in Nautilus Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.—which encourages patentees to take greater care to act as their own lexicographers and to resolve claim construction ambiguities at the drafting stage, 134 S.Ct. 2120, 2129 (2014)—the importance of extrinsic evidence to claim construction is only likely to decrease in the coming years.

Nonetheless, although Teva will not directly reduce the Federal Circuit's high reversal rates on claim construction, it is a vehicle through which the Supreme Court has expressed its dissatisfaction with the Federal Circuit's apparent disregard for the work of district courts. To that end, it is one of several recent messages the Court has sent to the Federal Circuit that it is a court of intermediate review, and neither a trial court nor an arbiter of last resort.

[1] See Cybor Corp. v. FAS Techs., Inc., 138 F.3d 1448, 1451 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (en banc).

[2] See Kimberly A. Moore, Markman Eight Years Later: Is Claim Construction More Predictable?, 9 LEWIS & CLARK L. REV. 231, 246 (2005), available here.

[3] From January 1, 2000 through mid-2005, the Federal Circuit reversed at least one claim term in over 40% of appeals and reversed, vacated, or remanded more than 30% of appeals based on an erroneous claim construction. See J. Jonas Anderson & Peter S. Menell, Informal Deference: A Historical, Empirical, and Normative Analysis of Patent Claim Construction, 108 NW. U. L. REV. 1, 40 (2014), available here.

[4] Fn. 3, supra, at 69 & n. 297.

[5] Fn. 3, supra, at 43.

[6] Vitronics, 90 F.3d at 1583 (“In such circumstances, it is improper to rely on extrinsic evidence.”).